WHY PORTLAND’S STREET GRID IS SO REVOLUTIONARY

Portland’s street grid was revolutionary not because it broke all the rules—but because it perfected them with elegant simplicity and foresight. When the original street plan was laid out in 1845 by founders Asa Lovejoy and Francis Pettygrove, Portland was a fledgling town on the Willamette River. But the grid they put in place—especially once refined and extended—set Portland apart from nearly every other major American city in key ways:

Compact 200-Foot Blocks

Most American cities followed the 300–400 foot block standard. Portland used 200-foot blocks, creating:

More intersections: fostering walkability and frequent street activity.

More corner lots: increasing property value and business opportunity.

Better solar access: with shorter buildings casting smaller shadows.

This block size promoted human-scaled urbanism far before that became a planning ideal.

Narrow 60-Foot Rights-of-Way

Portland’s 60-foot-wide street right-of-way (including sidewalks) was modest by 19th-century standards:

20-foot roadways flanked by wide sidewalks and planting strips.

Encouraged slower speeds, enhancing pedestrian safety.

Made it easier to cross the street and engage with storefronts.

This “tight and tidy” format became a model for modern infill and urban design.

Quadrant System and Cardinal Orientation

Portland is famously divided into quadrants (NW, SW, NE, SE—plus “North”):

Streets are aligned to cardinal directions, unlike many cities that follow rivers or hills.

Named and numbered streets make wayfinding intuitive (Burnside as baseline, Willamette as meridian).

This created legibility, a crucial asset in a pre-GPS era and still a boon for civic navigation.Recently Portland added a sixth ‘quadrant’ (or sextet) in South Portland.

Modular Expansion Across the Watershed

The grid expanded across rivers and hills with minimal deviation, particularly in East Portland:

Unlike other cities where grids warped with topography, Portland flattened and extended its grid across flatlands with consistency.

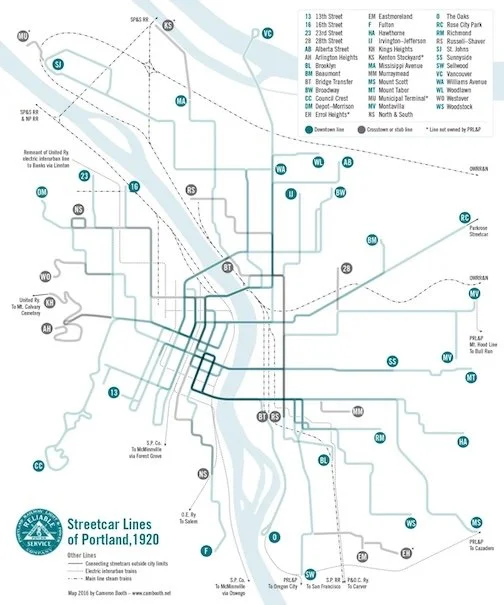

This allowed systematic planning of utilities, trolleys, and housing lots during the 1880s–1920s building boom.

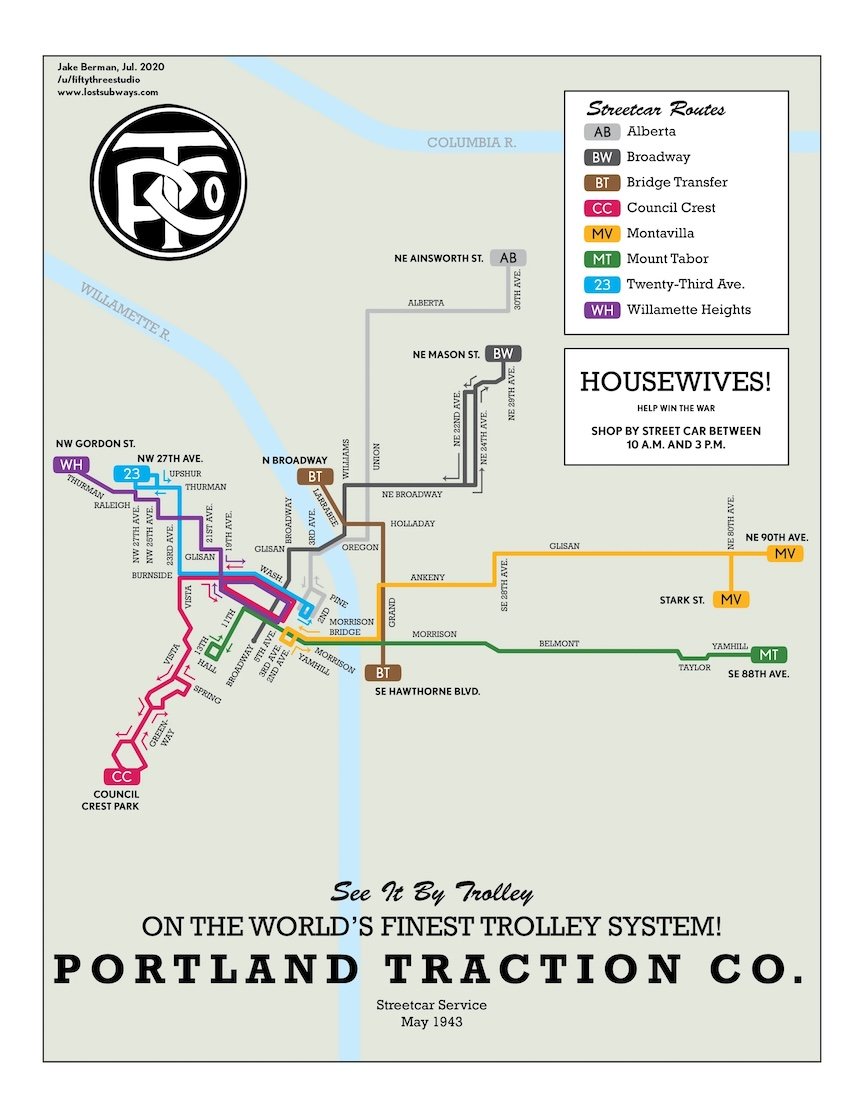

Transit-First Urban Form

Because of the small blocks and fine grain:

The grid supported frequent streetcar stops without disrupting traffic.

It allowed easy platting of “streetcar suburbs” in Laurelhurst, Sellwood, and St. Johns.

Portland’s streetcar grid wasn’t just transportation—it shaped development patterns, anchoring communities along its path.

Easy Subdivision and Infill

The simplicity of Portland’s grid made it easy to:

Subdivide land into narrow 25'x100' lots.

Build “skinny houses,” duplexes, and cottage clusters even today.

This gave Portland a remarkable level of development flexibility, enabling it to adapt more gracefully than cities bound by irregular blocks or topography.

A Human-Scaled Masterstroke

Portland’s grid was not about grandeur—it was about practicality, legibility, and livability. It enabled:

A walkable urban core with abundant street corners and storefronts.

An efficient transit system and adaptable housing framework.

A template for modern urbanism long before those terms existed.

In many ways, Portland’s grid anticipated 21st-century planning ideals. It wasn’t a revolutionary vision in its time—but today, it looks almost prophetic.

AND WITH GROWTH COMES CHANGE

as Portland grew beyond its original core, especially after the 1891 consolidation of Portland, East Portland, and Albina, the street grid began to shift in response to terrain, transit, and planning ideologies. These changes are visible in the differing block layouts and neighborhood patterns throughout the city. Here are key examples that illustrate this evolution:

Ladd’s Addition (1909) – The Anti-Grid

Design: Diagonal streets, circles, and rose garden medians

Why It’s Different: Inspired by the City Beautiful movement and European-style planning, Ladd’s Addition intentionally rejected the rigid grid to create a more scenic, residential neighborhood.

Impact: One of the first planned communities in the city, it introduced ornamental landscaping and curvilinear street design. It still confuses drivers—but delights urbanists.

Block layout: Irregular pentagonal blocks and circular intersections

Eastmoreland (Platted 1910s–1920s) – Garden Suburb Influence

Design: Curvilinear streets, long blocks, and deep lots

Why It’s Different: Reflects the early 20th-century trend toward garden suburbs, with winding roads and large homes on spacious lots. Streets follow natural topography instead of cardinal directions.

Impact: Less walkable than central Portland, but offers lush landscaping and privacy—attractive to the professional class.

Block layout: Longer blocks, no alleys, streets curve to match the land

West Hills Neighborhoods (e.g. Arlington Heights, Council Crest)

Design: Fragmented streets, steep inclines, switchbacks, and cul-de-sacs

Why It’s Different: Built on steep terrain where the grid was impractical, these neighborhoods were designed for cars and scenic views.

Impact: Street design prioritizes real estate value and aesthetics over connectivity. Very low walkability but high prestige.

Block layout: Nonexistent or irregular blocks due to geography

Streetcar Suburbs (Sellwood, Laurelhurst, Kenton)

Design: Grid-based, but adapted slightly for local topography and transit stops

Why It’s Different: Developed along Portland’s early 20th-century streetcar lines, these neighborhoods use modified grids to align with routes and parks.

Impact: Street orientation sometimes shifts slightly off cardinal directions. Often include “T” intersections, small parks, and boulevards.

Block layout: Modified 200x100 ft lots, occasional park-centered variations

Gateway and 1950s Suburbs (Hazelwood, Parkrose, Argay Terrace)

Design: Superblocks, cul-de-sacs, and arterial separation

Why It’s Different: Reflects postwar car-centric planning, with housing developments organized around collector roads and shopping centers.

Impact: Prioritizes automobile access, often lacks sidewalks or a connected grid. Built during Portland’s eastward suburban expansion.

Block layout: Superblocks with large lots, few intersections, disconnected side streets

City of Portland (OR) Archives, AP/94419

North Portland's Shift (St. Johns, Portsmouth)

Design: Some grid layout persists, but is disrupted by industrial zones, rail lines, and the Columbia Slough

Why It’s Different: Early platting in St. Johns preserved the grid, but later development around marine terminals and highways distorted continuity.

Impact: Shows the influence of industrialization and port access on neighborhood form.

Block layout: Mixed grids with industrial interruptions and larger parcels

What’s next for Portland? Townhomes and cottage clusters as urban infill will change the scale of the housing in some neighborhoods. Will the urban growth boundary be expanded to allow for new suburbs to crop up in Portland?